Bill Kent - A Carving Artist Remembered

by Alan BisbortBut, putting aside contemporary fixations with “value,” passing trends and fancies, one enduring truth remains: William Kent was a once-in-a-generation artist, a Brancusi or a Picasso, and he lived in a barn for the last 50 years of his life right here among us. He was, you might say, hidden in plain sight, his work ignored or rejected by museum directors, curators and art patrons who will now, more than likely, trip and fall over each other in their haste to buy his work.

Kent carved wood the way Brancusi sculpted: striving for the simple but profound beauty of form. Like buried treasures, hundreds of Kent’s carvings—most standing taller than he—are now stored under tarpaulins in his barn. They are everyday objects he re-creates in wood: giant shoehorns, pipes, ladles, vises, calipers, razors, safety pins, plugs, eyeglasses, corkscrews, shoes, light bulbs, shell beans, bell peppers (one fashioned into a “Self Portrait With Erection”), octopods, reptiles, dental plates. This was not whittling on a grand scale but was a complicated artistic process that produces all of five or six complete works per year. Defying belief, most of his sculptures are carved from single pieces of wood purchased from sawmills.

Speaking of Picasso, Bill Kent bore a passing physical resemblance to that artist and shared some of the master’s Promethean talent, as well as his penchant for not suffering fools. He once told me, “People look at my carvings and ask, ‘What can you do with it?’ How do you answer that? Wood carving is not fashionable. A narrow group runs the art world, and I don’t fit into it.”

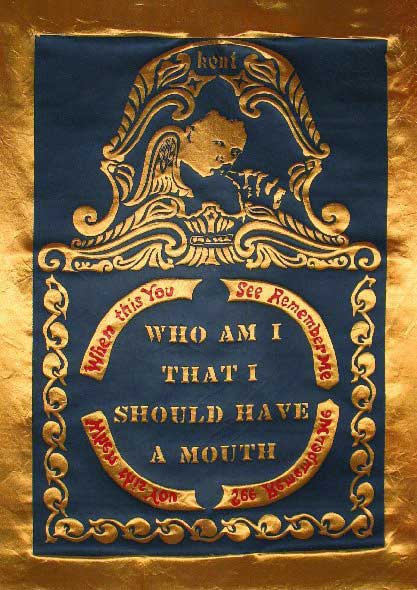

William Kent “Who Am I That I Should Have a Mouth?”

engraved-slate print on silk, 20″ w x 32″h

This calls to mind something Randall Jarrell once wrote about poets: “Tomorrow morning some poet may, like Byron, wake up to find himself famous—for having written a novel, for having killed his wife; it will not be for having written a poem.” Bill Kent wrote poems in wood and slate, but the world will not be featuring poets in ads for Louis Vuitton luggage. Kent, in fact, borrowed the words of the poet e. e. cummings for one of his slate prints that held pride of place above his bed; it was entitled “Honesty is the best poverty.” That line by cummings could well have been Bill Kent’s motto.

To those lucky few who knew Bill Kent even a little, however, his departure seems impossible. He seemed more a force of nature than a human being with a finite lifespan. But there it is: The great Bill Kent is gone.

Peter Hastings Falk of Madison, Conn. has devoted his career to resurrecting the work of neglected or lost artists. In addition to his 3-volume (and counting) opus Who Was Who in American Art, Falk has developed a massive data bank on auction price records for ArtNet.com, AskART.com and Artprice.com. Falk is dedicated to resurrecting the reputations and work of artists he calls “neglected,” and Kent was surely one of those. In the past several weeks, Falk had met with Bill Kent numerous times, prodding and engaging the artist to offer the biographical tidbits that had eluded the rest of us over the years.

Falk writes, “Kent was born in Kansas City, Missouri, in 1919. As a boy growing up during the Great Depression, he recalled that his father had some schooling but ‘never had a decent job’ and the family suffered. However, his father managed to buy an upright piano for a few dollars; and, after a series of free piano lessons his young son immediately fell in love with making music. A few years later, young William had saved enough money to pay ‘Miss Peach’ fifty cents a lesson, and soon he was playing opera scores. An avid reader, by sixteen he had read James Joyce’s Ulysses, and was placed in the accelerated classes in his high school, which allowed him to earn college credits.

“In 1940 Kent was drafted into the U.S. Navy, and served at the Naval Station at Great Lakes as a stock clerk for almost three years. In 1942 he entered Northwestern University but upon graduating in 1944 was left ‘completely unstimulated by the experience.’ However, the rich cultural life of Chicago with concerts, museums, and visiting performances by the Ballets Russes and the Metropolitan Opera opened new worlds for him. Returning to his love of music for inspiration, and using the G.I. Bill, he entered the graduate program for music theory and composition at the Yale University School of Music. He was energized by Paul Hindemith, the great modernist German composer and theorist who had fled to the United States in 1940 because the Nazis had deemed his work “degenerate.” During this period Kent made many friends from the Yale Art School and came into intimate contact with their sculpture, painting, and printmaking. Soon, Kent was experimenting with both sculpture and painting. It was while immersed in his music studies that he came to experience what he called ‘the visualization of sound’ and began to relate it to his art.”

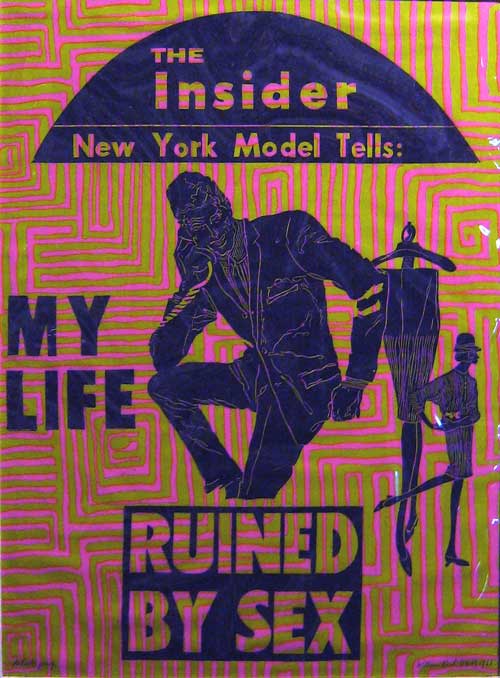

William Kent “My Life Ruined By Sex”

engraved-slate print on silk, 18″ w x 28″h

After Kent received his master’s degree in music theory and composition from Yale in 1947, he stayed in New Haven and was invited by the Dean of the Yale Medical School, Milton C. Winternitz, to set up a studio in his basement, where he lived for the next year. Here he began sculpting stone, plaster, clay, cast stone, driftwood and marble. From there, it was a logical progression to carving in huge slabs of 200-pound slate that he found at a demolition company and had transported to his barn studio in Durham, where he’d moved in 1965.

His work was included, alongside other promising “new” artists like Jasper Johns, Helen Frankentheler, Robert Motherwell and Robert Rauschenberg in the 1965 Whitney Biennial and he was represented by renowned art gallery owner Richard Castellane gallery in New York. But, after a controversy ensued over some of his erotic prints, he was relieved of his job as the first curator at the John Slade Ely House in New Haven, at which point he washed his hands of the art community. Like the resume of an ex-convict, Kent has some long, inexplicable gaps in his chronology. Actually, that gap covered the last 50 years of his life, during which time he worked daily creating his prints and sculptures in his barn in near anonymity (in fact, someone else’s name was inscribed on his mail box, perhaps to keep the world further at bay).

As he once told me, “You do your art and then die. That’s the way the world wants it.”

It is not just that Bill Kent was a recluse—though undeniably he preferred his own company to anyone else’s. That is too pat, too comforting an explanation for the neglect that greeted the world’s greatest carver of wood. No, Bill simply did not want to spend one minute doing something other than working on or thinking about his art. During his 50s, when he should have been able to live on his art, he preferred taking a job in a box factory to hustling his art on the “street.”

He grew weary of the “poor old man, curmudgeon, recluse” angle the media seemed to prefer when confronting someone in his predicament. This approach, he said, implies that his work was “not good enough to sell, probably not commercially viable in the first place, because everyone knows that if an artist is good, he sells.” Kent bristled at the suggestion that he was ‘hiding’ his work and could produce a lengthy document itemizing every rejection he had received since 1980. He kept these rejection letters in his office—thick folders of correspondence with museum directors, gallery owners, curators, potential art patrons. Among the typical responses was one from Wesleyan (University) Art Gallery: “We have to have credentials, Mr. Kent.” Or another from the New Britain Museum of American Art: “repetitive.” Or one from the lowly Mystic Seaport Gallery: “We want something small we can sell.”

Kent cannot be blamed for recoiling at the process of approaching these sorts of second-rate venues. But what really hurts is the utter silence from the places where his work should be: the National Gallery of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, the Hirschhorn, the Guggenheim, the Corcoran and the Whitney.

After a while, he hardened his shell to this and simply stopped sending out queries. Bill Kent was not plagued or paralyzed by self doubts. He knew he was a great artist, locked into his own idiosyncratic vision. He could have allowed the bitterness to fester and stop him—and if you asked him about it, he would unload a lifetime’s worth of frustration for your elucidation—but he had bigger fish to fry or carve.

“Modern art has triumphed,” Kent told me years ago. He viewed his contemporaries like Johns, Warhol and Lichtenstein as “the fashionable interior decorators of our time. When they teach modern art in the Yale School of Design, you know it’s finished, a dead style. I can remember when I came to Yale School of Music in 1944; modern art had not touched Yale. They had a guy there called Eberhard, who said he studied with Rodin. That was the style they worked in at that time—tempera painting from the Renaissance to the late 19th century. All of a sudden, they flipped over and went modern when Joseph Albers came in the 1950s.”

In recent years, Kent has unenthusiastically enlisted the aid of art agents, with mixed success. He gave up the effort when one of them booked him at an “outsider art” exposition. “I seem to be ‘outside,’ so to speak, because my work is so highly finished. People look at it and say, ‘Oh, it’s craft work.’ Craft work? That’s crazy. Look at a piece like this,” he says, unwrapping a breathtaking work from 1961 of a man kneeling with a wasp and praying mantis on his back, all carved from one piece of black walnut. And another work, from 1964, of a mahogany hand holding an alabaster cricket. And another, from 1968, of a water faucet with a chain flowing from its spigot—all made from one piece of cedar. Still another, from the same year, of an eagle with a duck’s face seated on a trash can that has tires so realistic you have to feel them to be sure they’re wood; at the duck’s feet is a perfectly rendered egg in alabaster, a zipper running along its top. “They don’t seem to accept this as art,” he said. “That’s what I’m up against.”

There is some solace to be had from the fact that Bill Kent went out in the manner and place that he wanted—still working every day in his barn studio in Durham, still planning future sculptures, surrounded by a lifetime’s worth of art that never, but should have, sold.

In a way, it was a miracle that he had the last six years of his life to work at all. That is, in 2006, he suffered a debilitating circulatory condition resulted in the amputation of his right leg above the knee. One would think this would convince an 87-year-old artist to throw in the trowel, but Kent was undeterred. Fueled by his own irascible determination and his artistic vision, Kent spent the his final six years doing what he’d done since he decamped from New Haven in 1964 to his Durham barn. He was, literally, on his last leg but he kept going.

Bill Kent Memorial Gathering

Contact the Foundation

Studio Location

269 Howd Road

Durham, CT 06422

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from the William Kent Charitable Foundation.

Please check your email to confirm the subscription.